“Rashid Johnson is recognized as one of the major voices of his generation, an artist who composes searing meditations on race and class while establishing an organic formal vocabulary that fuses a variety of sculptural and painterly traditions. The Rainbow Sign takes its name from the same African American spiritual that inspired James Baldwin’s title for his seminal 1963 book The Fire Next Time. The works in the show pose questions about how symbols of national identity and social belonging are constituted, as well as what it might mean to shake free of them. They also offer embodied metaphors for the act of making oneself heard in the context of a group, whether as an act of protest, self-advocacy, or unbridled expression.

Amplification of the voice is an organizing principle for a series of wall-based sculptures, shown here for the first time, that function as working microphones. In addition to the microphone components themselves, each consists of a series of bronze shelves adorned with the mark-making and hand-drawn symbols characteristic of Johnson’s visual language. They house a variety of objects, including books that offer accounts of African American experiences (Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time and Claudia Rankine’s Citizen among them). Johnson does not consider such objects “found” things; they are chosen, rather, for specific visual and textural qualities in addition to their pre-existing content. He arranges multiple copies of the same book in stacks or rows, for instance, to create a serial linearity that borders on abstraction.

Once activated, these works create the potential for dynamic engagement, and represent a significant evolution of the shelf sculptures that heralded a major advance in the artist’s career almost ten years ago. This will become particularly clear during the opening, when renowned poet and playwright Ntozake Shange and acclaimed musicians Kahil El’Zabar, Alex Harding, Ian Maksin, and Corey Wilkes will perform before them. Each artist will enter into dialogue with a single sculpture, turning his or her back to the audience but providing sound that will be amplified for a large gathering of people. As a result, both the performances and Johnson’s artworks facilitate conversation about the fragile balance between solitude and social immersion–seemingly antithetical states of being that are as necessary for artists as they are for any active member of a healthy democracy. After the performance and throughout the run of the show, the sculptures will remain live. Viewers’ voices and other ambient sounds will be amplified and become a palpable force in the space.

Alongside the microphone sculptures, Johnson will debut a second new body of work. Entitled Broken Men, these are teeming compositions made from irregularly shaped ceramic and mirrored tiles that in turn provide the support for gestural applications of spray paint, oil stick, and the black soap and wax mixture that has become a hallmark of the artist’s practice. While tile has been an important material for Johnson since the beginning of this decade, he employs it here in a way that is diametrically opposed to how he has used it in the past, when its primary function, visually speaking, was to establish a rectilinear grid. Now, with the tile broken, the grid is ruptured and itself transformed into a picture-making medium. The jagged pictures in question are stylized busts the artist has previously termed “anxious men”; their rectangular heads, twisted mouths, and swirling, agitated eyes lend them an archaic universality that would feel equally at home scrawled on building exteriors in a contemporary city or the interior walls of a prehistoric cave. And just as Johnson has taken things one step further in material terms, these men are no longer just anxious, but broken–anonymous figures representative of a moment when ordinary life feels structurally unstable.

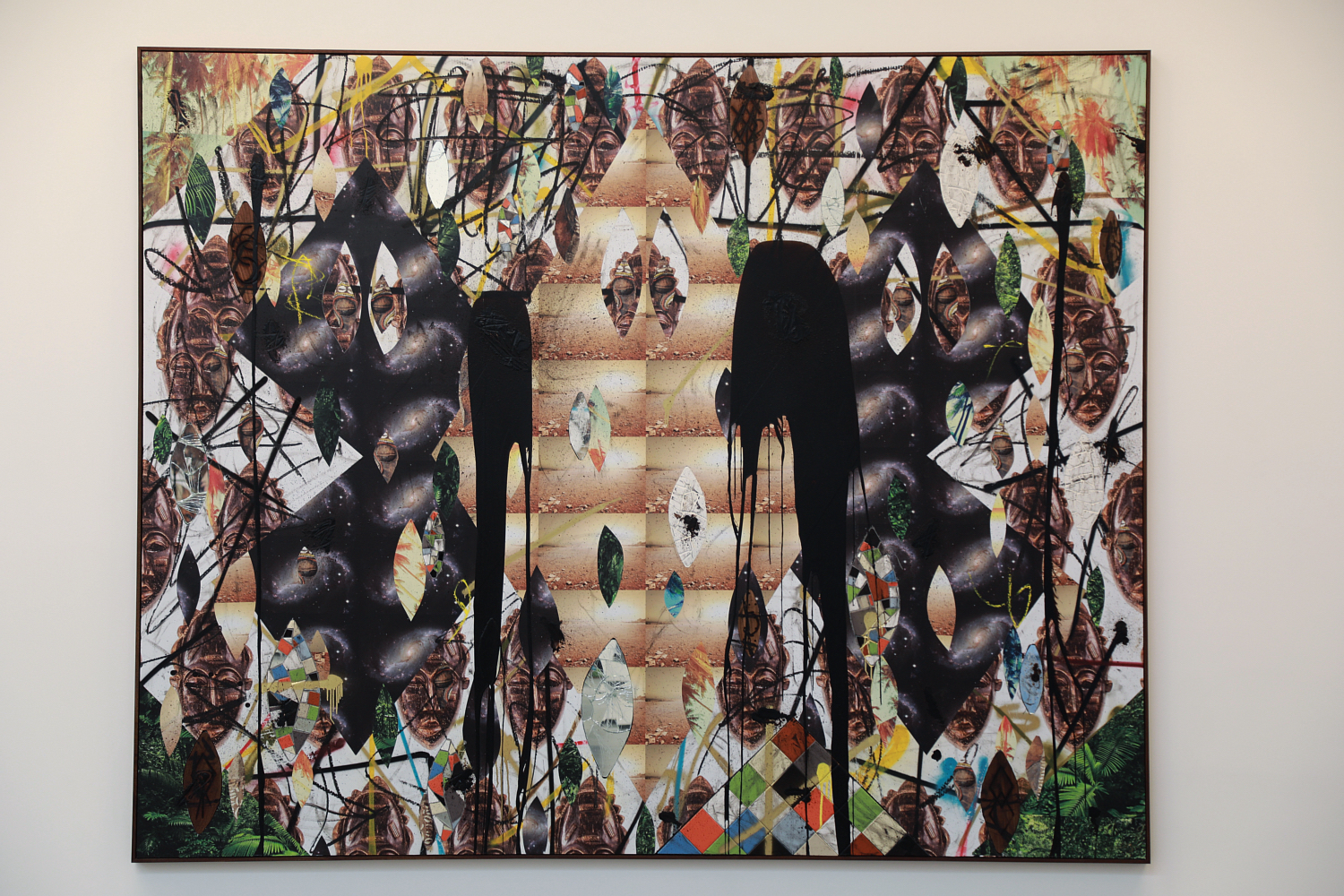

Another gallery will house the latest examples of Johnson’s large-scale Escape Collage paintings. Featuring photographic images of indigenous masks, beach scenes, and tropical foliage arranged into complex geometric patterns alongside embedded tiles, the collages depict kaleidoscopic visions of imaginary landscapes. Not unlike the science fiction fantasies of Sun Ra, their imagery is associated with dreams of escaping the local, the urban, and the familiar. They point toward a romantic (and elusive) paradise: a zone of great natural beauty, a speculative African American homeland, and an otherworldly realm free of social and economic inequality. At the same time, Johnson’s frenetic approach to mark-making–with energetic lines scratched into black wax, cracked tiles, and broad areas covered in graffiti-like spray-paint–roots the work squarely in a dystopian here and now.”