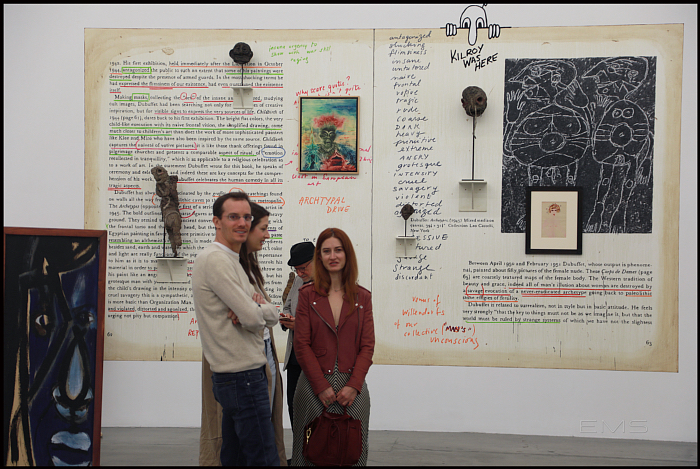

Blum & Poe is pleased to present New Images of Man curated by Alison M. Gingeras.

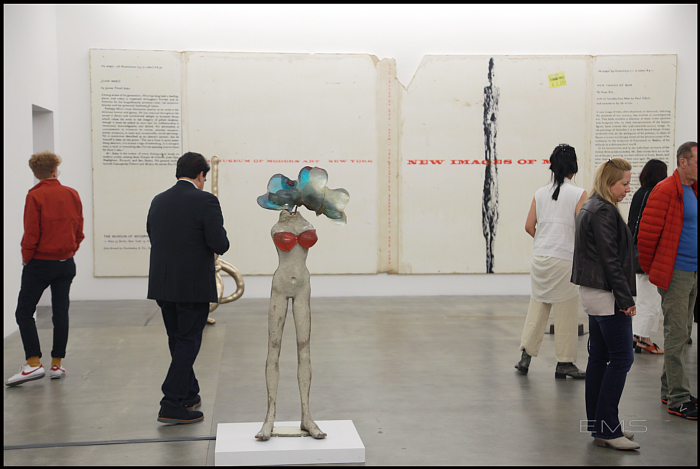

This exhibition revisits and expands upon the Museum of Modern Art’s eponymous 1959 group exhibition curated by Peter Selz that brought together artists whose work grappled with the human condition as well as emerging modes of humanist representation in painting and sculpture in the wake of the traumatic fallout of the Second World War.

Some sixty years have passed since New Images of Man presented key figures of the European neo avant-garde such as Alberto Giacometti, Jean Dubuffet, César, Francis Bacon, and Karel Appel alongside the ascendant figures of the American art scene such as Willem de Kooning, H.C. Westermann, and Leon Golub. Set against the backdrop of existentialist philosophy and the socio-political anxieties of the postwar period, the esteemed humanist philosopher Paul Tillich wrote of these artists in the original MoMA catalogue, “Each period has its peculiar image of man. It appears in its poems and novels, music, philosophy, plays and dances; and it appears in its painting and sculpture. Whenever a new period is conceived in the womb of the preceding period, a new image of man pushes towards the surface and finally breaks through to find its artists and philosophers.”

Part homage, part radical revision, this two-floor presentation reconstitutes emblematic figures from the original MoMA line up of artists while simultaneously expanding outwards to include those of the same generation and period who were overlooked in the midcentury. This reprisal features forty-three artists hailing not only from the US and Western Europe, but also Cuba, Egypt, Haiti, India, Iran, Japan, Poland, Senegal, and Sudan. The overwhelming maleness of the original New Images of Man has been amended by foregrounding previously excluded women artists from the same generation. Had gender politics of the 1950s been less misogynist, Selz might have considered artists such as Alina Szapocznikow, Niki de Saint Phalle, Yuki Katsura, Carol Rama, and Lee Lozano. With the benefit of inclusive hindsight, Gingeras strives to present a fuller range of this humanist struggle, thus more acutely enacting the original curator’s vision to gather a range of “effigies of the disquiet man.”

As the capstone to this historical proposition, the exhibition argues for the contemporary resonance of this midcentury disquiet by judiciously including a selection of contemporary artists. These living artists are also “imagists that take the human situation, indeed the human predicament” as their primary subject, while also reflecting the legacy of the aesthetic concerns from the original period. Spanning painting and sculpture, this contemporary component includes works by Paweł Althamer, Cecily Brown, Luis Flores, Michel Nedjar, Greer Lankton, Miriam Cahn, Sarah Lucas, Dana Schutz, El Hadji Sy, Ahmed Morsi, Henry Taylor, amongst others.

Installed alongside these paintings and sculptures, historic and contemporary, are interventions that evoke the larger-than-life figures from the original show—de Kooning, Dubuffet, Bacon, Giacometti, Westermann. Playful tributes to these masters appear throughout the exhibition, including two wall murals by Los Angeles artist Dave Muller.

Embedded at the center of this revisionist enterprise is another historical MoMA exhibition also founded upon postwar humanism—this time through the lens of photography. The 1955 exhibition Family of Man curated by Edward Steichen—the legendary director of the Photography Department at MoMA—was conceived four years before Peter Selz’s New Images of Man, and was devised as a celebration of the camera as a powerful, immersive tool for the promulgation of images as well as the affirmation of the universal human experience. While it debuted in New York in 1955, Family of Man went on a veritable world tour. According to Steichen’s 1963 memoir A Life in Photography, between 1955 and 1962 about nine million viewers all around the world had the opportunity “to see themselves reflected” in the 503 photographs of people, making it the most popular photography exhibition ever.

As the legacy of Steichen’s curatorial endeavors lives on in contemporary visual culture, this section of the exhibition sets out to challenge the Western-centric bias of the original show. This reassessment of Steichen’s conceit focuses upon two women artists from the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The Polish, self-taught photographer Zofia Rydet was active in the mid-1950s yet she was separated from Steichen not only by the Iron Curtain. This redux presentation of Rydet’s photographic oeuvre suggests a more complex vision of postwar era humanist photography. In fact, after seeing Steichen’s Family of Man show in Warsaw, Rydet embarked upon her series of documentary images of children in the literal rubble of the Second World War in the early 1960s entitled Mały człowiek (Little Man). This presentation features a selection of Rydet’s photographs from her documentary series called the “Sociological Record” in which she captured thousands of ordinary households in Poland from 1978 until her death in 1997.

Rydet’s reworking of the Steichen paradigm finds a jarring echo in the contemporary oeuvre of Deana Lawson—an artist whose intimate, yet iconic imagery immortalizes African-American family life. Lawson grew up in Rochester, New York, the birthplace of Kodak—her involvement with photography is deeply bound up with her family’s history and their entwinement with the photographic industry. Unlike Rydet, Lawson’s images are often staged while they strive to capture the magic and textures of everyday struggles, emotions, and plain existence. Her gaze intrepidly focuses upon members of the African diaspora while also crafting stunning formal compositions that hark back to classical painting. As Lawson has said of her work, “I have an image in mind that I have to make. It burns so deeply that I have to make it.”

Shown side by side in a scenography that references Steichen’s original Family of Man presentation at MoMA, Rydet’s communist-era documentation of Polish families in their humble interiors resonates uncannily with Lawson’s present-day portraiture. Despite being decades apart, culturally disparate, and approaching their medium with radically differing methods, both Rydet and Lawson create images that offer a sharp rebuttal to Steichen’s sentimental and melodramatic original opus. Both photographers share a quality that Lawson has articulated when speaking of her own work, creating images that are “thick with space, layered with otherness and belonging at the same time.” Together Rydet and Lawson provide a revisionist twist to this new Family of Man. This section of the show was curated in collaboration with Antonina Gugała with a new installation by Deana Lawson made especially for the show.

While much has changed in social and political terms since the 1950s, we are arguably again in a period of immense existential questioning and profound collective anxiety—artists now, as then, are on the frontlines of confronting what it means to be human, therefore making New Images of Man a subject still urgent for contemplation and provocation. This past summer, Selz died at the age of one hundred. In his New York Times obituary, his daughter Gabrielle remarked, “He would say that everything—a somber painting by Rothko or a Rodin sculpture—was about the human condition. My dad responded to emotion.” Arguably, emotion is the gravitational force that draws us to images of other people—from prehistoric cave paintings to press photographs of detained refugees and children on the Mexican-American border, humans find empathetic connection, solace, or simple recognition in the act of contemplating depictions of other humans. In the spirit of Selz’s original aim, this restaging of New Images of Man and reimagining of Family of Man resolves to recontextualize artists’ agency in addressing the fundamental questions of the human condition and to discourage apathy about our fellow humans’ plight.

While an art exhibition can only operate on a symbolic and discursive level, the impetus behind the new New Images of Man is to continue our collective rumination on the human condition with renewed emotional and intellectual urgency. By expanding the geopolitical and generational scope of artists, an expansive vision of humanity starts to emerge—broadening “man” to a more intersectional vision of human existence.

– for more information on additional images from this event please contact EMS at emsartscene@gmail.com or Instagram at @ericminhswenson